By Father Thomas Esposito, O.Cist.

Special to The Texas Catholic

Being a father requires a man to acknowledge his mortality. From a purely biological perspective, the sexual drive is a program for reproduction that presumes the death of the one generating new life. Leon Kass, a brilliant physician and philosopher, asserts this truth in a stark manner: “Sexual desire, in human beings as in animals, points to an end that is partly hidden from, and ultimately at odds with, the self-serving individual: sexuality as such means perishability and serves replacement. The salmon swimming upstream to spawn and die tell the universal story: sex is bound up with death, to which it holds a partial answer in procreation. This truth the salmon and the other animals practice blindly; only the human being can understand what it means.”

The Greeks and Romans, among other ancient peoples, knew this truth terribly well. Without a clear sense of an afterlife, immortality was attainable only in partial ways: by leaving descendants who passed down the family name and boasted of their ancestors’ glorious (or infamous) deeds throughout the generations.

Being a father requires a man to confront his own helplessness. As the child develops slowly in the mother’s nurturing womb, the father can only watch passively, unable to assist in any concrete way. His desire to shield his children once they are born from all dangers, whether physical or spiritual, is both noble and impossible to fulfill.

Being a father requires a man to stand silent before the mystery of life. His virtuous example, in words and deeds, of patience, justice, protective and sacrificial love, is necessary and life-giving, sometimes even life-sustaining, to his wife and children. But he must find in the quiet times, when the children are asleep and he is alone with his thoughts, a refuge inviting him to prayer.

God is revealed in Scripture as Father, the eternal origin of life. On the natural level, the closest perfection to God that human fathers can attain is to imitate the divine creativity, cooperating with God in welcoming new life into the good but wounded world. Though all earthly fathers are marked by selfish sin, they nevertheless make possible the formation of their children in the ways of unselfish love, which unites them with the Father and the communion of saints.

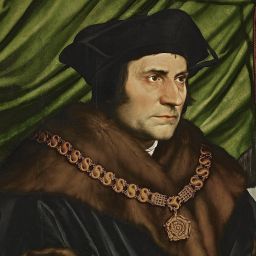

Jesus Christ is the eternal Son, the image of the invisible God who learned obediently as a human being from Joseph, his earthly guardian. This righteous man’s silence in the Gospels speaks eloquently of his sacrificial devotion on behalf of the Son who transcends all earthly categories. The quiet obedience of St. Joseph teaches us that paternal strength resides not in our weak wills or our illusory ability to control a situation, but in the certainty that God seeks humble and persevering servants.

This is not a typical celebratory Father’s Day meditation; no Hallmark card will feature such apparently dour reminders to Dads of their limitations, weaknesses, and mortality. But the privileges and challenges of imitating both St. Joseph and the eternal Father of Jesus Christ make fatherhood an awe-inspiring vocation. To find the true medicine of immortality, and to teach their children to love this remedy, is an immense challenge for Christian fathers today. The privilege is that we already possess this antidote to death; around 110 A.D., Saint Ignatius of Antioch defined it as the Eucharist. Fathers must see in the Body of Christ the pattern of sacrificial love that they to imitate. To accept their weakness, and to learn how to relinquish the control they do not have in the first place to the Lord, are further challenges for Christian fathers. The privilege in this regard is that the vulnerable trust demanded of them is expressed beautifully in the quiet life of Saint Joseph, and contained in the prayer of the father who asks Jesus to heal his possessed son: “Lord, I do believe; help my unbelief” (Mark 9:24).

Father Thomas Esposito, O.Cist., is a monk at the Cistercian Abbey of Our Lady of Dallas and teaches in the theology department at the University of Dallas.