In 2007, on the Feast of the Chair of Peter, Pope Benedict XVI gifted us with his first Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation. The title in Latin, Sacramentum Caritatis, in English, The Sacrament of Charity, or as I prefer, The Sacrament of Love.

This summer Catholics around the world are invited to participate in two exciting, inter-related events in the life of the church. The World Day for Grandparents and the Elderly will take place July 23, and World Youth Day is being celebrated in Lisbon, Portugal during the first week of August.

In my last column I discussed the cardinal virtue of temperance and how it assists us in regulating our desires for pleasure. In this column I want to continue with the conversation about the cardinal virtues because of their essential value in our moral lives. Prudence is one of the cardinal virtues and a very important one to practice and to acquire both as humans and as people of faith.

I recently accompanied a group of University of Dallas students and young alumni to the Holy Land, and I would like to share some musings about Christian faith and pilgrim feet based on that blessed experience.

In a world of insatiable pleasures, temperance is the ultimate saving virtue. Temperance is the virtue that enables a person to have a balanced spirituality and a balanced life. In the Catholic Church, temperance is described as one of the cardinal virtues. Temperance uses reason to moderate or restrain our desires and the pleasures of our senses.

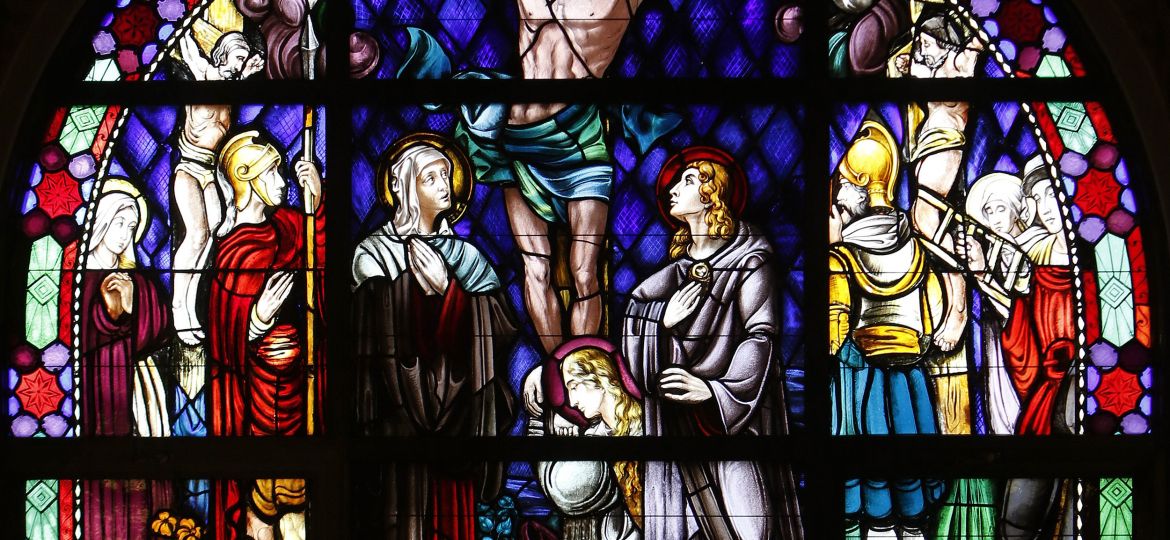

May is the month that we honor the Blessed Mother in our lives. This is a long-honored tradition that has been celebrated in the Church for centuries.

Spring, according to custom, is a most suitable season for weddings; the abundance of freshly bursting flowers signals that creation rejoices in the beginning of a new life together. The Easter season, overlapping with spring, often features priestly ordinations; the abundance of Alleluia joy reverberates through cathedrals as men are uniquely consecrated for the Lord’s service. Every ordination conveys a jolt of hope to a diocese or religious order. The sight of new priests around their bishop signifies that the Lord continues to channel grace through chosen mediators who link believers today back to the Apostles.

Every year we commemorate the season of Lent, which culminates with the celebration of Easter. This is always a reflective season that helps us examine our spiritual lives, identify with the suffering of Jesus, and share in the glory of His resurrection at Easter. During the season of Lent many of us resolve to model our lives on the example of Christ. During Lent, Christians take up Lenten observances such as fasting, almsgiving and prayer, and many Catholics abstain from several things in order to attach themselves more closely to God. Some of us gave up certain behaviors, foods, practices and places as part of Lent. Now that Lent is over and Easter Sunday has come and gone, what next? What happens to our abstinence, those things we gave up? What happens to the renewed prayer life that we had during Lent? What happens to our acts of charity and almsgiving that we exercised during Lent? Are they going to be our new way of life, or will we abandon them and go back to our “former ways”?

Over two millennia of Church history, several standards of orthodoxy have served as the pillars on which a correct understanding of the Christian mysteries must be built. One of them is what I would call the incarnational principle: a proper acknowledgement of the goodness of the material world and the human body.

“Why should I be happy?” I wasn’t expecting such a snappy retort to my friendly question “Are you happy?”, even though the respondent was my scowling confrere Father Roch Kereszty. Never satisfied with facile and clichéd conversations, Father Roch always resisted the shallow and automatic answers we give to questions that are usually superficial, but can often contain profound depths.