By Father Thomas Esposito

Special to The Texas Catholic

St. Benedict concludes the Prologue of his Rule for monks with an uplifting exhortation: “Do not be daunted immediately by fear and run away from the road that leads to salvation. It is bound to be narrow at the outset. But as we progress in this way of life and in faith, we shall run on the path of God’s commandments, our hearts expanding with the inexpressible delight of love.” For Benedict, the monastic life is a school in which the monks, who graduate only at death, never cease learning how to love the Lord. The relentless rigors of work and prayer stretch the heart, pushing it outward and generating an ever-greater capacity to love and be loved.

If the love of God enlarges the heart, the antithesis of that love, fear, contracts it. Saint Benedict rephrases the insight of 1 John 4:18-19, without doubt the biblical verses I most frequently share with those who come to me for spiritual direction: “There is no fear in love; rather, perfect love casts out fear […] We love because God first loved us.”

The standard signs of fear at work in an individual are the inability to be at peace in the present moment, and to doubt the desire of God to love and guide you. In this regard, a fruitful meditation can be had in thinking of the heart as the present moment. The constantly fleeting “here and now” is our closest experience to the timeless eternity in which God dwells, and the essence of prayer is the relationship between two people present to each other.

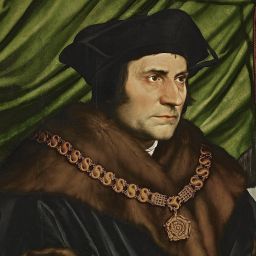

St. Francis de Sales describes the mystery of prayer with the beautiful phrase cor cordi loquitur, “heart speaks to heart”:

“Truly the chief exercise in mystical theology is to speak to God and to hear God speak in the bottom of the heart; and because this discourse passes in most secret aspirations and inspirations, we term it a silent conversing.

Eyes speak to eyes, and heart to heart, and none understand what passes save the sacred lovers who speak.”

But fear sabotages prayer and the peace of the present moment by crushing the heart with forces coming from different sides of the timeline. The past obliterates the present when I allow regrets, disappointments, and a guilt-heaping sense of failure to crowd out any thought of my own goodness or ability to accept that God’s love is indeed unconditional, even for my self-caged self. The future crashes into my now when worries and consuming uncertainties buzz around the brain in hypothetical phrases beginning with “What if” and “Yeah, but” and “I should do more…” The simultaneous attack of past shame and future anxiety constricts the heart so tightly that the present moment virtually vanishes. Such a squeezing of the heart produces only isolation, and a deadened inability to give and receive love.

Yet the present moment is precisely the gift, the location, the time in which God wishes to meet me!

This psychological mechanism is marvelously displayed in the story of Jesus encountering the despairing disciples on the Emmaus road (Luke 24:13-35). On Easter morning, two people are walking away from Jerusalem. Their disappointment and sorrow are so complete that they are fixated on Good Friday and bereft of hope for the future, even though they heard a report that very morning that Jesus’ tomb was empty. As a result, they do not recognize the Lord, who walks with them and teaches them how to read the Scriptures in the light of his resurrection. But when they share a meal together, they recognize him “in the breaking of the bread” — the first post-Easter Eucharist. Their experience of time thus changes: as Jesus walked and ate with them, his presence became their present moment, the sole focus of their entire being. After he vanished from their sight, their past was filled with his sweet memory, and their future was charged with the hope of seeing him again. Their exclamation about the presence of Jesus is the word for everyone who experiences a crushed heart, or the coldness of an extinguished flame of love: “Were not our hearts burning within us as he talked to us on the way and opened the Scriptures to us?” (Luke 24:32).

Father Thomas Esposito, O.Cist., is a monk at the Cistercian Abbey of Our Lady of Dallas and teaches in the theology department at the University of Dallas.